Teaching Kids Not to Romanticize Teasing: A Parent’s Guide

Here’s why kids’ teasing shouldn’t be romanticized as a form of love

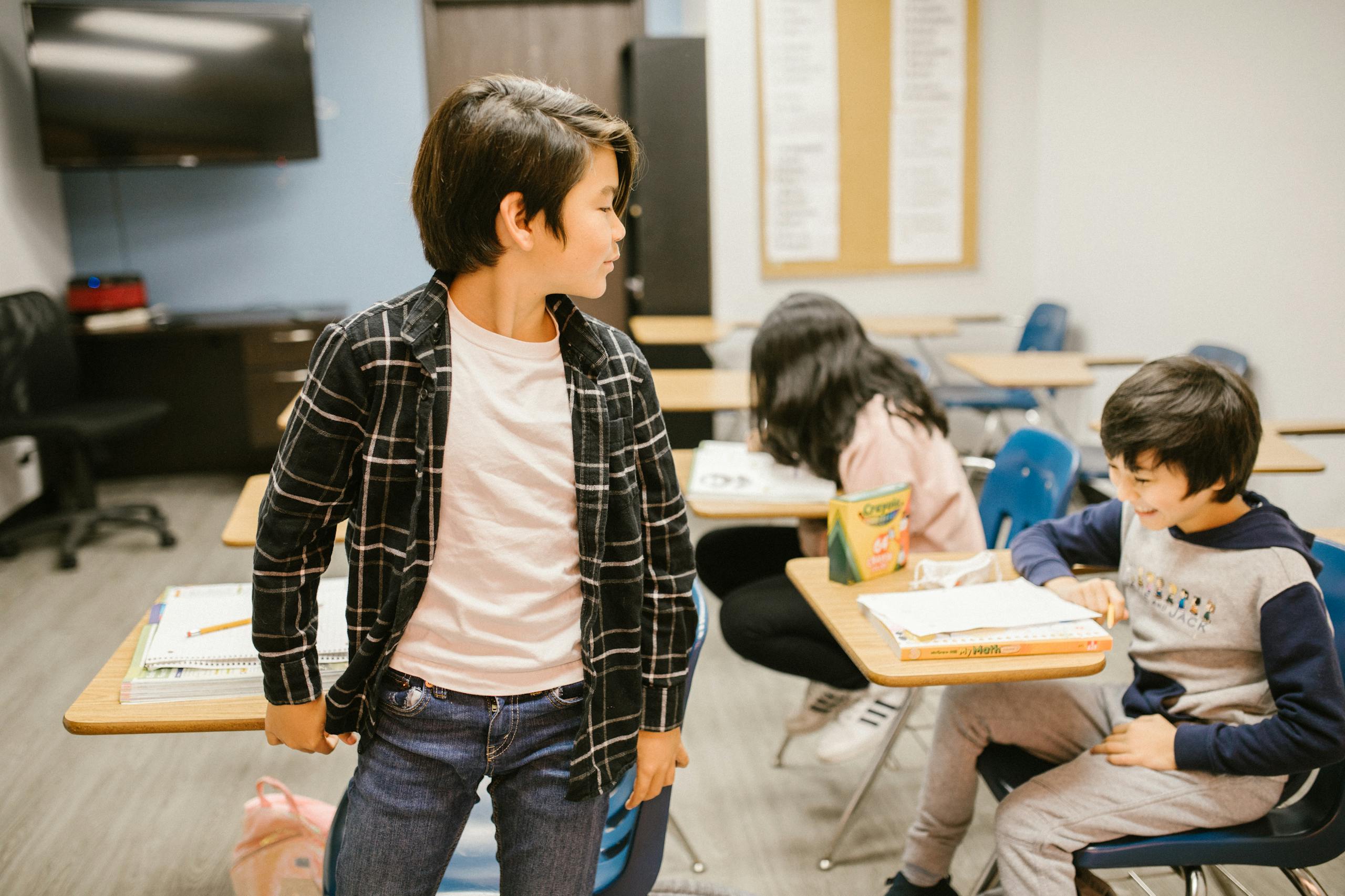

Many Filipinos often romanticize with an “uyyy!” or two that teasing and playful banter often show up as harmless expressions of kilig, gigil, or love. It’s common to joke with nephews, tease siblings, or even respond with a light “biro lang” (just kidding). But beneath the laughter lies a subtle communication challenge: teasing and sarcasm aren’t always understood by kids the way adults intend — and they’re not healthy substitutes for real expressions of love and connection.

As parents, we have to separate culture from communication and intention from impact.

Why Kids Don’t Always Get Teasing the Way Adults Do

Very young children, especially under around age 5, are still developing core social and language skills. While toddlers may respond to teasing with smiles, that’s often recognizing familiar interaction, not understanding the intent or meaning behind the tease. Research shows that understanding ambiguity in social language, like teasing or sarcasm, takes time and cognitive skills that develop over the years.

Sarcasm, in particular, is one of the more advanced forms of language. It requires a child to hold two ideas at once — the literal words and the underlying intention — which develops gradually as cognitive skills mature. Studies suggest children may begin detecting ironic intent around 5–6 years old, but full appreciation and accurate interpretation come later and vary widely.

Adding to the complexity, teasing can be a double-edged sword. When playful (like siblings nudging each other lightly), it may build social connections. But when it targets personal traits — appearance, ability, behavior — it crosses into harmful territory, potentially damaging a child’s self-esteem or sense of belonging.

In the Philippine context, where humor is a social glue and teasing is an everyday expression, teasing can unintentionally mask hurt, especially for kids who are still learning emotional cues beyond literal phrases.

Kilig vs. Confusion: When Playful Turns Painful

Children often interpret language very literally. Unlike adults, they don’t instinctively read emotional subtext behind tone or kidding phrases. While parents may intend a tease to be lighthearted, a child might take it at face value, which often leads to confusion or even distress. That’s especially true for sarcasm, where the “real message” contradicts the words spoken.

Understanding this difference matters because teasing doesn’t always communicate love. In developmental psychology, teasing and sarcasm are treated as forms of indirect communication — and for children who haven’t fully developed the capacity to decode emotional intention, it can feel like criticism instead of affection (Dawes and Andrews, 2025).

From Kilig to Clarity: How to Talk Without Harming

To help children develop healthy emotional expression and communication skills, consider these shifts:

- Use clear language over jokes when addressing emotions.

- Teach kids why you say certain things—especially if teasing is cultural or familial.

- Model gentle humor and affirmations over sarcasm or ironic comments.

- When teasing occurs, follow up with direct emotional labeling (e.g., “I’m joking, and I care about you”).

- Be mindful of developmental stage; young children (below age 7–8) may interpret literal meaning first.

Teasing Shouldn’t Be Seen As A Love Language

While teasing isn’t inherently negative, it’s when parents romanticize it as innocence or kilig, without guiding children to understand intent and impact, that problems can start to crop up. Sarcasm and teasing can mask hurt, confuse developing minds. Worst of all, that sends mixed messages about what love really feels like.

Language is children’s first emotional environment. Teaching them clear, kind communication — not just teasing as affection — helps them internalize secure emotional signals early in life.

References

Dawes, M., & Andrews, N. C. (2025). What are the Features of Playful and Harmful Teasing and When Does it Cross the Line? A Systematic Review and Meta-synthesis of Qualitative Research on Peer Teasing. Adolescent Research Review, 1-30.

MAZZOCCONI, C., & Priego-Valverde, B. (2025). Humour from 12 to 36 Months: Insights into Children’S Socio-Cognitive and Language Development. Available at SSRN 5022663.

Pexman, P. Why it’s difficult for children to understand sarcasm. (2021, June 10). News. https://ucalgary.ca/news/why-its-difficult-children-understand-sarcasm

Frequently Asked Questions

Because most likely, it isn’t. Plus, it also teaches them that making people feel bad about themselves is a form of love—which let’s be honest, it’s not.

Research suggests basic teasing may be recognized by toddlers, but sarcasm — as a form of verbal irony — becomes understandable as cognitive and social skills develop, typically after age 6.

It’s a common love trope that the Japanese have dubbed the tsundere kind of love. It’s romanticized that their inability communicate their true feelings usually manifests in the form of teasing or blunt commentaries.

Not always. Playful teasing among close friends or family can build bonds, but teasing about personal traits, differences, or vulnerabilities can hurt self-esteem and trust.

Watch your child’s reaction — confusion, withdrawal, or distress can signal they’re taking it literally or negatively. Never assume they “get it.”

More about teaching kids about love?

How Emotional Safety Becomes a Child’s First Love Language

Andi Manzano: Learning by Language of Love

How Kids Understand The 5 Love Languages