Real Talk

10 Lessons The Boy and The Heron Teaches About Grief and Losing Loved Ones

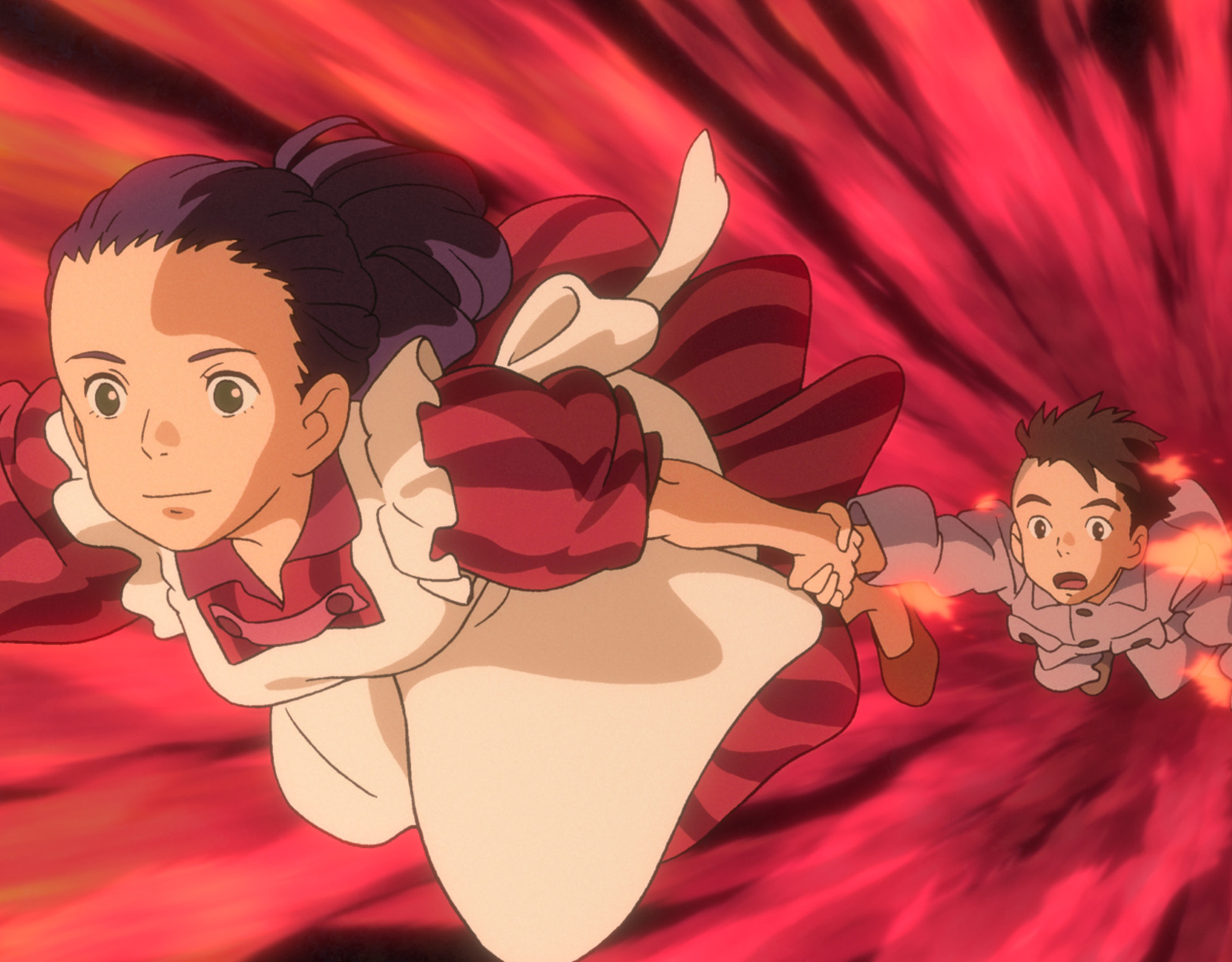

Hayao Miyazaki’s latest work, The Boy and The Heron, teaches valuable lessons about grief and dealing with the loss of loved ones.

Studio Ghibli’s Hayao Miyazaki always made family-friendly films with deep philosophical meanings and themes behind them with this movie being no different. With the release date of The Boy and The Heron‘s English dub on January 8, 2024, in the Philippines, some of us couldn’t wait or wanted to enjoy it in its original language: Japanese.

Taking place during the Pacific War in Japan, The Boy and The Heron tackles mostly the theme of grief and how to deal with the swirl of emotions that accompany it. The movie, also containing some elements from Hayao Miyazaki’s childhood, candidly confronts the theme while offering comfort through these lessons.

10 Lessons We Learned From Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and The Heron

1. There will always be a resistance to change.

When Mahito loses his mother at the beginning of The Boy and The Heron, his reception and responses to Natsuko, his stepmom, are indifferent at best. He keeps his replies, monosyllabic and simple. Sometimes, the loss of a loved one makes us so numb that we can’t come up with a proper sentence. It takes too much energy to engage a person who’s trying to learn about us.

It’s only with a lot of coaxing, especially from different people, that Mahito finds the energy to engage Natsuko.

2. Everyone deals with grief differently.

Mahito and Shoichi both deal with the loss of Himi, Mahito’s mom differently. While Shoichi falls in love with Himi’s sister, Natsuko, Mahito withdraws. Grief sometimes makes us seek out companionship but it can also isolate us at the same time. The two characters demonstrate both possibilities, either we are looking for someone who understands our pain or we believe that nobody understands so we hide.

3. Grief makes us more open to trying something new, even if it’s dangerous.

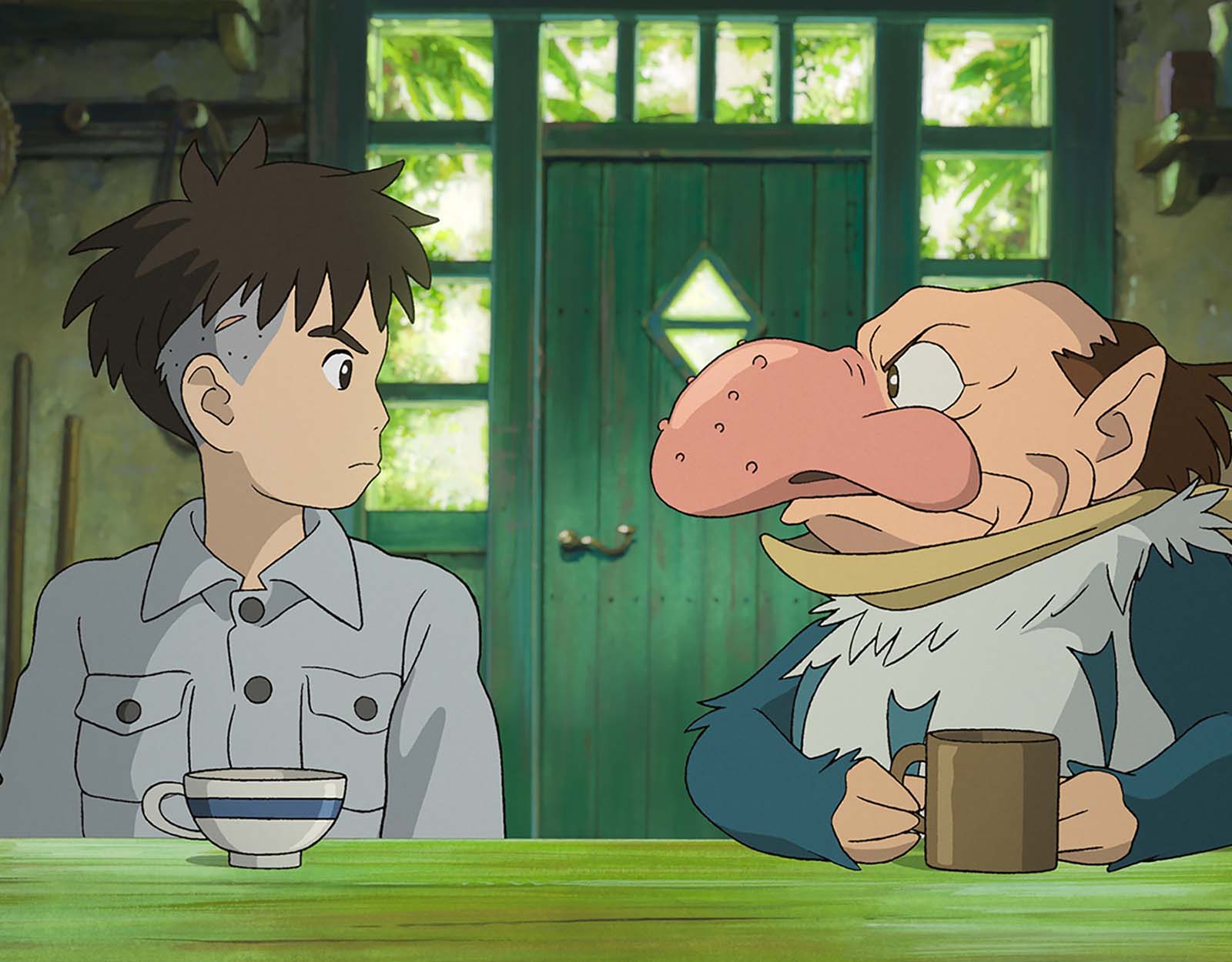

While we can chalk Mahito’s going to the tower as unwillingness to accept Natsuko as his new mom, we can also see that his curiosity also gets the best of him. Especially when the Gray Heron (voiced by Robert Pattinson in the English dub) lures him to the tower, he ignores Natsuko’s and Kiriko’s (one of the old maids) warnings and further chases the heron.

4. We will do everything we can to bring that loved one back.

Although Mahito goes deeper into the tower to bring back Natsuko, his initial curiosity comes from hearing that his mom is looking for him. In the Japanese dub of The Boy and The Heron, the heron taunts him saying, “Mahito, tasukete.” which if translated into English means “Mahito, help me!” but more in the save one from danger context.

Although he at first denies the possibility, Mahito eventually caves and fashions himself a bow made of bamboo, rice, string, and the heron’s feathers. He also then bribes one of the old blacksmiths in the house with a packet of cigarettes to teach him how to sharpen his knife which he uses in the tower.

Of course, the idea of someone coming back from the dead is impossible to believe. But when we’re in grief, it offers a glimmer of hope that we may achieve closure or perhaps, return things back to normal. For Mahito, normal was going back to Tokyo with his mom, Hisako.

5. When in grief, sometimes, we feel “malice.”

When grief leaves a void filled with unanswered questions and numbness, sometimes, we fill it with malice. We’re angry at the circumstances that we’re left with; we feel estranged in a situation wherein there is no assured way to control things.

When Mahito went to school, his frustration led him to retaliate with a fistfight against farmer boys who were bullying him. He then makes it worse by smashing a rock against his temple, leaving a scar. Upon arriving home, he then lies to both Natsuko and his father about where the scar came from.

Our grief makes us want to explode but when there’s no one to take it out on, we take it out on ourselves. Although Mahito explicitly hurt himself, sometimes, we can indirectly hurt ourselves by drowning in work, alcohol, or just anything to take away the grief. We look for a way to swim above that numbing grief and sometimes, the best way to do so is with pain — both physical and mental.

6. At one point, we will have to face the ugliness of our grief.

We often respond to grief with love, support, and compassion. But in The Boy and The Heron, Mahito’s confrontation of his grief is more candid: facing his own inner turmoil when he meets Natsuko in the tower’s delivery room. Originally, she doesn’t respond to his calls but it’s only when he calls her “mother” that she does.

But when he does for the first time, she responds with an embittered scream, “I’ve always hated you!” as if to mirror his own rage. Our grief can sometimes be so blinding that we will hurt others because we are fixated on trying to make our pain go away.

7. Grief doesn’t always end cleanly.

Watching slice-of-life dramas on the silver screen may have somewhat taught us that grief can be dealt with cleanly but, The Boy and The Heron shows it differently but in a funnier way: bird droppings. Almost every moment in the movie, there is an instance when Mahito, Shoichi, and even, Natsuko end up covered with bird droppings as if to show that grief and life always have a messy aspect. Even if there is no reason to be [messy]!

8. Grief sometimes makes it hard to tell what is real and what is dream-like.

Grief, being a strong emotion, kind of seats us on the fence between the real world and the dream world. Kind of like Alice in Wonderland, Mahito ends up traveling through the world within the tower which pays tribute to various fairytale elements: the Heron acts similarly to the Cheshire Cat from Alice in Wonderland, the grannies of the house remind us of the doting 7 dwarves from Snow White with Kiriko representing Grumpy, the talking and human-eating pelicans and parakeets…

So, it is true: grief can drive us insane!

9. The loss of a loved one can mark a new journey of discovery.

What do we do when a person we truly love is gone? With our identity so closely knit to theirs, their dying feels crippling. We find ourselves confused and lost; we dig deeper into our souls and find what we can be without them. Mahito’s journey into the tower has him connect with other members of his family, including his great grand-uncle who’s the tower master, and even his mother as a child, Himi.

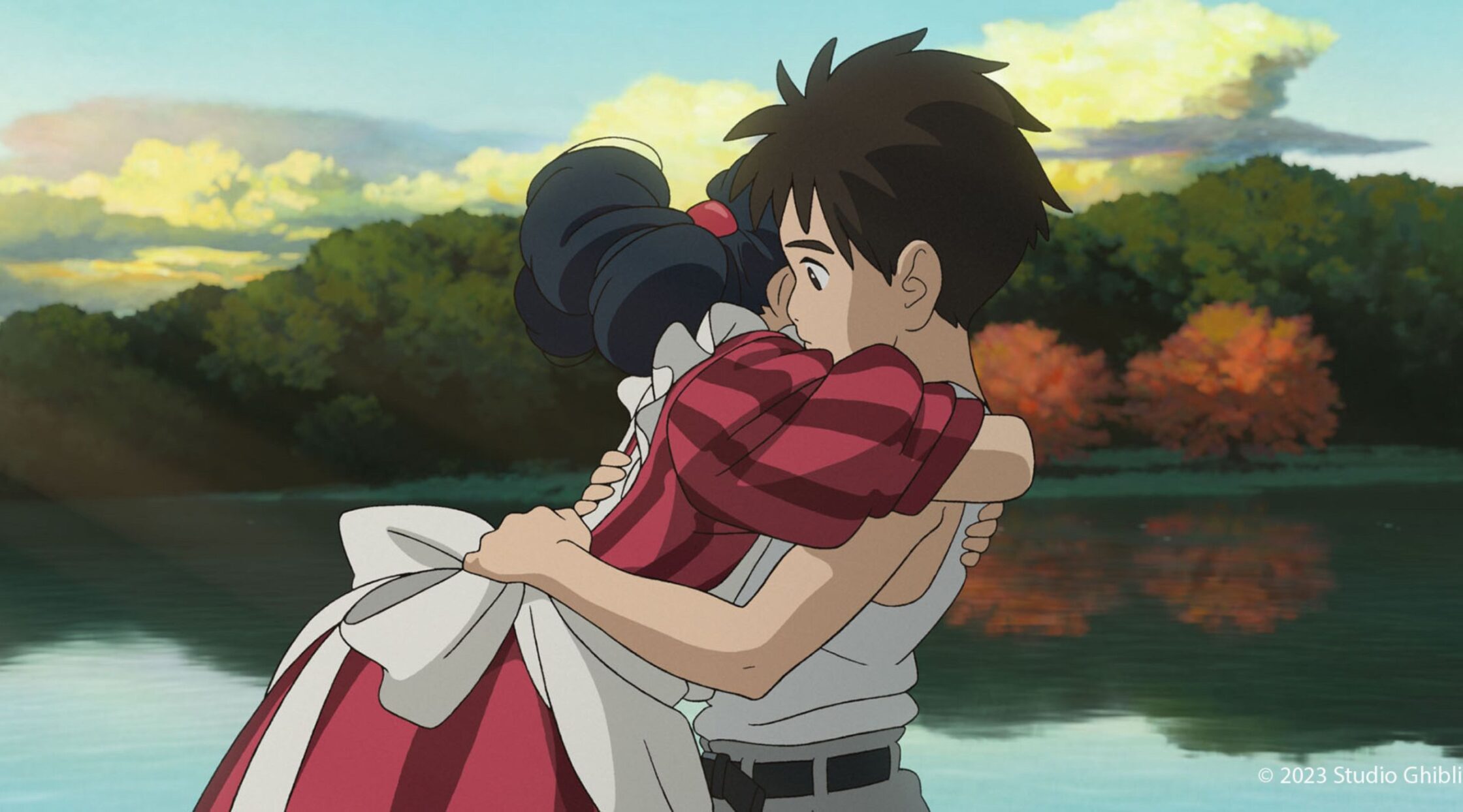

His short journey with Himi, who reveals in the end that she was Hisako, perhaps served as a closure to his initial identity as he tearfully bade her goodbye, watching her go through a door while accompanying Natsuko through another.

10. To finally let go, it’s a choice we have to make ourselves.

We can’t let go of our grief on someone’s command; it’s something we have to be comfortable with. When the heron tells Mahito to take no keepsakes, it’s a sign of letting go of the world where he had met his mother. Although the wooden doll he had in his hand was the old maid Kiriko, he also leaves the block that he took along, watching the heron and parakeet assuming their natural and wild forms.

The Boy and The Heron candidly tells the tale of about grief and acceptance.

The movie is quite unlike Hayao Miyazaki’s earlier works such as Kiki’s Delivery Service and My Friendly Neighbor Totoro, following a darker narrative similar to his environmentally-inspired movie Princess Mononoke. But that’s because there is no romanticizing or sugar-coating grief; healing is a messy process in which we struggle in trying to fly above it. Yet once we do, there is a lot of growth to be had.

The release date of the English dub of The Boy and The Heron in the Philippines will be on January 8, 2024! For families who need a book or a movie to console them when they lose their loved ones, this movie will walk it through with you.

The movie also pays tribute to its basis and original title by adding a cameo of the 1937 novel by Genzaburo Yoshino, How Do You Live (Kimi tachi wa do ikiruka?).

More about movies?

Rewind is a Reminder for Couples That Time is of Essence

4 Reasons Why Wonka Is A Must Watch By Kids

5 Lessons Kids and Teens Can Learn From the Film GomBurZa